The 20th annual conference of the North American Travel Journalists Association, held in Fairbanks, Alaska, in May 2023, ended on a high note, indeed. It represented the culmination of a 16-day journey that included travel by air, cruise ship, bus, and train. The route took me from my home in Arkansas to Vancouver, British Columbia, then north along the inland passage to Alaska’s port cities, and on to Anchorage, Denali National Park and inland Alaska.

At the conclusion of the conference, I was off on another type of adventure — a grueling ride along the Dalton Highway, a mostly unpaved roadway that loosely follows the route of the Trans-Alaska pipeline from just north of Fairbanks to Deadhorse, Alaska, on the Arctic Ocean. It is barren, uninhabited land.

Our guide and driver told us that in the 1980s, a group of homesteaders had formed a small community in an “off-the-grid” location along the route. Today, even they have moved on, with only a handful of buildings as testimony to their former lifestyle. We stopped at what was once the general store in the area, now owned and maintained by the tour company as a convenience stop for participants on the Highway excursions. The site’s several buildings stand empty and unused, but there are clean, well-maintained outhouses, complete with lighting and framed art on the walls. It was not only a welcome rest stop, but the site offered numerous photo ops as well!

Leaving Fairbanks, we traveled along the Stease Highway, then joined the Elliott Highway (roadways in Alaska have names rather than numbers) until we reached the Dalton Highway, made famous by the television show, “Ice Road Truckers,” for the long-haul drivers who bring food and supplies to oil field workers and support crews along Prudhoe Bay.

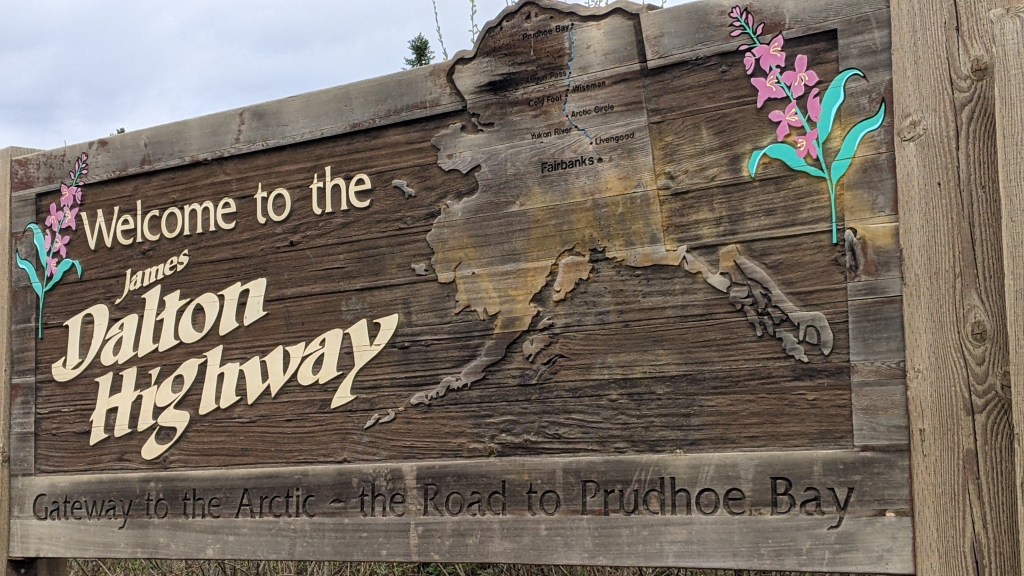

There is a welcome sign where the Dalton Highway begins. At a stop there to take photos, we met a couple of motorcyclists traveling north from California to Deadhorse!

The Dalton Highway stretches 414 miles north from Livengood, a former gold mining town approximately 80 miles north of Fairbanks to Deadhorse, Alaska., at the Arctic Ocean. Originally known as the North Slope Haul Road, it was begun in 1974 and completed in just five months to facilitate pipeline installation. The pipeline itself stretches approximately 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to its terminus at the ice-free port of Valdez in Prince William Sound. Still a marvel of engineering, the Trans-Alaska pipeline was operational in just 20 months, and began pumping oil in 1977.

The highest mountain in this northern region is just over 3,200 feet (in contrast to Denali’s height of more than 20,000 feet only a few hours to the southwest). The high point on the Dalton Highway is 2,200 feet, but much of this land is above the tree line, and it appears stark, nude, and forbidding in its solitude.

Hilltop Gas Station, 15 miles outside of Fairbanks, is the northernmost source of fuel until drivers reach Coldfoot, on the Yukon River, or the northern terminus of Deadhorse. The power line also ends not too far north of Fairbanks. In a very real sense, this is “the end of civilization.” Pedro Dome, situated northeast of Fairbanks, provides the only Doppler weather radar tracking for the entire state. If it goes down, weather forecasts for Alaska are only guesses.

Our second stop was at Yukon River Camp, where pipeline workers, roadway maintenance crews, and truckers gather. It serves as rest stop, information and communications center, local store, no-frills eatery and is a welcome sight for the few tourists along the lonely road. There is a small village of support personnel, with overnight accommodations available.

Visitors can check the weather, make phone calls, grab a hot cup of coffee, even purchase sweatshirts, postcards, and souvenir magnets. It was here that we once again met the cyclists and wished them well on their continued journey north.

Cities in this northern inland portion of the state are non-existent; even primitive settlements are few and far between. Water, power and fuel do not exist, and travel is treacherous.

Although our excursion traversed not quite half the length of the Dalton highway, we traveled far enough north to literally leave civilization behind. It was a unique experience.

Later, our group stepped across the latitude line (66 degrees, 33 minutes) that marks the Arctic Circle, and we celebrated with “Alaska mud cake” and whipped topping at a picnic table in the forest — under the watchful eyes of curious squirrels and hopeful “thieving birds” perched just above us in the trees. It was there that we picked up a handful of southbound travelers, adventurous souls who had previously ventured further north and would be returning with us to Fairbanks.

On our return south, we stopped again at the Yukon River Camp. But now the kitchen was closed, and the staff had gone to bed. We brought our own sandwiches or microwavable dinners. Water and hot coffee were available to us, but there was little else other than tables, chairs and clean rest rooms. The camaraderie made up for the late-night lack of service.

My colleagues and I — participants in this unique post conference Dalton Highway press trip — discovered the uninhabited, “ungoverned wilderness” of far north inland Alaska. I was overwhelmed by the isolation, and enthralled by the beauty of the land. Only a limited number of participants were chosen for this unique tour offered by the Northern Alaska Tour Company. Another somewhat less-strenuous option offered to Alaska tourists provides an alternative overnight stay near Coldfoot, Alaska, in the Brooks Range, a bumpy hour or so north of the Arctic Circle. On that excursion, travelers can opt to take a morning hike along the Yukon River, followed by a bush-plane flight back to Fairbanks. Fellow journalists who took part in that trip reported that the return flight was spectacular, not to mention a few hours of welcome sleep in a rustic cabin with a comfortable bed!

We traveled through the northern boreal forest that spans the globe from Alaska to Scandinavia. Russia and Asia boast greater biodiversity and life forms; in Alaska, there are only four species of trees that grow in the permafrost: white and black spruce, aspen, and birch trees. Because we were there in spring, we witnessed the aspen and spruce leafing out, even though snow remained on the ground in some areas. We were told that a few weeks earlier, the land was fully blanketed with deep snow. But spring comes quickly to this part of Alaska.

For my part, though, I was grateful for the opportunity to learn from our knowledgeable guide about the history of the Trans-Alaska pipeline and its current upkeep and operation. I was impressed by the ongoing maintenance work along the mostly unpaved roadway, even though construction delays late at night were a bit unnerving! I felt a slight sense of fear, tempered by awe, each time a swirling cloud of dust signaled the approach of a speeding 18-wheeler.

Those long-haul drivers are experienced, professional and, usually, extremely courteous. But it is obvious they operate on an unforgiving timetable, and they simply “keep on trucking.”

I was duly impressed by the sight of the 45-year-old, mostly-elevated oil pipeline as it snakes across the land. For more information about the construction and continuing operation of this engineering marvel, visit TAPS Construction -Alyeska Pipeline.

We stopped for a short time at an outcropping of granite tors, huge natural outgrowths that stand like sentinels on the barren land. Much further to the south, there is a 15-mile trail and public campground at another tors site, maintained and administered by the Alaska Division of Parks and Outdoor Recreation.

This trip is by no means an excursion for the faint of heart. But neither was it, as a participant on a tour prior to mine proclaimed, “the worst day of my life.” It was long, yes; cold, drizzly, uncomfortable, and tiring. We returned to our Fairbanks hotel at about 3 a.m. for a few hours of sleep before flying out that afternoon to the Lower 48. Would I do it again? No, but I’m certainly happy to have had the full experience.

It was a ride I will not soon forget! And the changing hues of blues, pinks, and striated yellow and orange that filled the night sky in those late night and early morning hours will forever color my memories of far north Alaska, a land full of wonders and surprises.

The certificate I was presented proclaims that I crossed the Arctic Circle and “survived an adventurous journey through the Alaska wildnerness.” That says it all!