Last May I wrote about a 2018 visit to this city in Normandy against the backdrop of the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landing. We were still in the early days of the pandemic. Two months ago, the world marked the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Today we are engaged in another battle against a formidable virus. On November 11, we honored those who serve or have served in our military. Today, we still await a definitive answer to the question of who will be our next president. Through all of this, I cannot help but remember my visit to Rouen. It serves as a reminder that generations of our forebears survived wars, devastating plagues and years of civil unrest. They endured. And so will we. Rouen adds new perspective to contemporary history. Perhaps we should learn from it.

The heart of a great city

William, Duke of Normandy, became King of England in 1066 following his victory at the Battle of Hastings, and the course of history was forever altered for two nations, if not for the entire world. Known today as William the Conqueror, his coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, but soon after his investiture, he returned to the capital of Normandy.

Considered a military genius, he was a descendant of the Viking Rollo, was uneducated, lacked culture, and spoke little English. He returned to England to quell periodic uprisings, but he spent most of his reign on the continent. He died near Rouen at the age of 60, in 1087, and is buried near the coast, at Caen, France, in the The Abbey of Saint-Étienne which was founded in 1063.

Another Duke of Normandy, who also held the titles of Duke of Aquitaine and Gascony, and Count of Anjou, was born in England, the fifth son of King Henry II and Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine. He led a turbulent life, rebelled against his father the king, and formed an alliance with the king of France, along with two of his brothers.

Richard I was crowned King of England in 1189, but spent little time there. Like William the Conqueror, he may not even have spoken the language, but he was educated, enjoyed music and the arts, was personable but temperamental and quick to anger. He was also obsessed by the Crusades. He reigned for less than 10 years, and is best remembered for his exploits in the Holy Land, fighting Saladin and the Saracens during the Third Crusade.

Richard the Lionheart, not quite 42 years old, died of an infected arrow wound in 1199. History recounts that he had always “held Rouen in his heart,” and his embalmed heart rests in Rouen’s Cathedral, while his body is entombed “at the feet of his father” at Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. His younger brother John succeeded him on the English Throne, and Phillip II of France gained control over Rouen, assuring that Normandy and Brittany would remain under French control.

I knew of the historical ties Rouen has with these renowned English kings, but it was yet another historical figure that beckoned me to Rouen. The Maid of Orleans met her destiny in Rouen in 1431. She was tried for heresy, witchcraft and other offenses ranging from horse theft to sorcery. She was burned at the stake by the English in a square that still serves as the site of the city’s public market. Her bones and ashes were gathered and thrown into the river.

History recounts that Joan of Arc did indeed hear voices and see visions. She believed they were signs, but modern authorities suspect she suffered from a medical disorder, something akin to epilepsy or perhaps schizophrenia.

Although characterized as a warrior, she actually never fought in battle, choosing to simply accompany the troops carrying a banner to urge them on. Nonetheless, she is credited with turning the tide of battle and securing a French victory over English forces in Orleans in 1429.

Joan was originally charged with 70 crimes which were later narrowed to 12; it is said that she signed an admission of guilt in exchange for life imprisonment, but days later violated the terms of that agreement by, among other things, once again donning men’s clothing and admitting that “the voice” had returned to guide her. She was subsequently sentenced as a “relapsed heretic,” according to historical records.

Joan of Arc — the name stems from her father’s surname d’Arc, even though she was simply known as Jehanne or Jehannette. During her trial, she referred to herself simply as Jehanne la Pucelle (translated as Joan “the maid”).

The young peasant girl became a national symbol, a uniting influence on French forces during the latter part of the bitter 100 Year’s War that lasted from 1337 to 1453. There actually was no victor in the war; the English simply retreated, finally realizing that the cost was too great, and the conflict ended.

Twenty years after the war ended, Charles VII, the French king who owed his position to Joan, held a posthumous retrial to clear her name, and she became not only a folk heroine, but also a mythic symbol of French nationalism.

As a child I was fascinated by her exploits, and by her brazen defiance of existing norms. I am still fascinated, and I wanted to see for myself the place where she met her fate.

For centuries, there was no monument to mark the spot of her demise in Rouen, just a simple cross in commemoration of the 19-year-old’s martyrdom. Today, a large modern Catholic church stands to honor Saint Joan; it was completed adjacent to the square in 1979.

Joan, by all accounts, never doubted that she had been chosen by God for her role in history, but it was not until 1920 that she was canonized as a saint. Today she is revered as the patron saint of France.

Then and now

Rouen is filled with good restaurants, small cafes and local bakeries. It boasts boutique hotels tucked away on narrow streets, within walking distance of major sites, a newly-redesigned and attractive riverbank that beckons river cruisers and bicyclists, picnickers and artists. Prior to the pandemic, visitors from across the globe arrived in the city during every season, seeking their own fulfillment. Rouen’s cultural appeal is catholic, and it resonates on different levels depending on one’s personal interests.

But Rouen offers something else as well. Visit the city during the off-season, and a uniquely personalized view of the city is your reward. The pace of life in this part of France is easy-going and friendly, surprisingly subdued. Indeed, if you stay in the medieval quarter or the university district, the slice of life that presents itself is distinctively “common.” It’s truly delightful, relaxed and unpretentious.

One can walk seemingly endlessly through the narrow cobbled streets of the Medieval quarter. We marveled at the clock, standing under its archway one dismal, chilly late afternoon. We lingered, snapping pictures, studying the artistry of its face and enjoying the music of its chimes. We knew that darkness would soon descend, but we hesitated there, unwilling to break the mood.

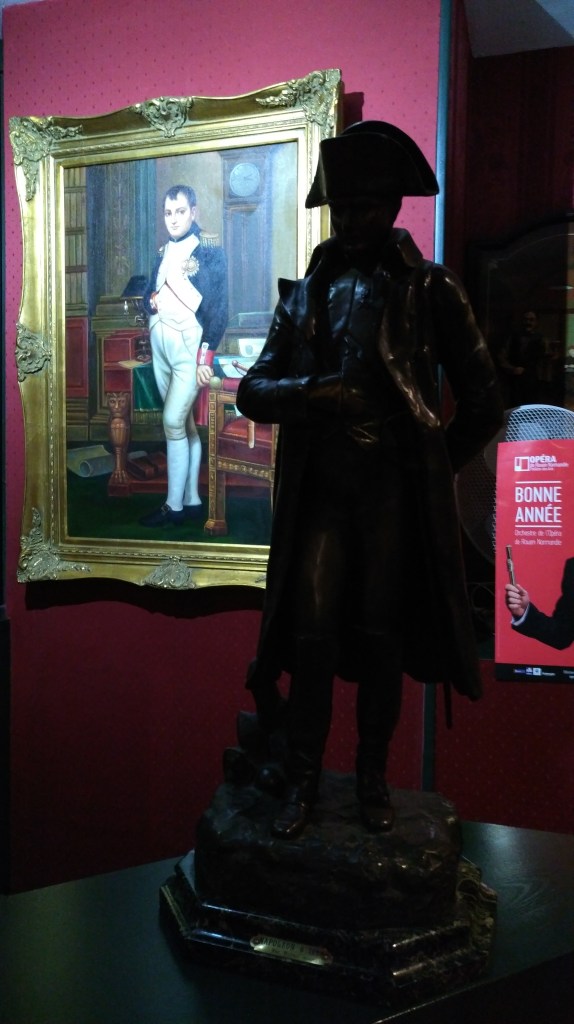

It’s impossible to be in Rouen and ignore its past. Napoleon visited textile factories in the city in 1802, helping to build that industry in the region; he also is credited with commissioning the Corneille Bridge and both Lafayette and Republic Streets. In Rouen, it is impossible to escape the emperor’s historical influence. In numerous ways, the history of France is tied to the history of Rouen.

Seeing it all unfold during a walking tour of the city is spellbinding. The most enduring memory, however, is of being alone in the courtyard of Rouen’s ossuary, the “Plague Cemetery.” It is an experience seared into my consciousness, as the world faces an unknown future besieged by a seemingly unstoppable virus.

Later, we ducked into a small brasserie for a cup of hot cafe au lait, and exchanged small talk with the proprietor and two other patrons who were as happy to speak a few words of English as we were to practice our French. We were immediately transported to the present, and we were buoyed by the charm and vivacity of the city’s modern vibe.

We left, strolling the almost deserted streets in search of an informal place to eat. Arriving too early for dinner, we were led upstairs to a warm, cozy nook that suited us perfectly for an early-evening supper. We sipped good red wine, dined on burgers and fries served in true French style, and conversed with the establishment’s friendly proprietor about contemporary life. It was a perfect finale to a day of immersion in the life of Rouen.

We will long remember our visit to Rouen, for a good number of reasons.