Haint Blue

It’s a paint color, a pale, watery shade that seems somehow imbued with sky, water, serenity, and the hopes and dreams of an entire culture. It’s traditional for the Gullah Geechee inhabitants of Georgia, the Carolinas and the sea islands that extend along the Eastern seaboard all the way to northern Florida. These people were transplants from western Africa, primarily Angola. For them, the color blue was sacred.

In their native land, and also in the new world as enslaved people, they worked indigo plantations. The distinctive blue dye derived from indigo plants was used for textiles and was also adopted for home furnishings and décor. The Gullah people frequently painted the trim on their dwellings or the ceilings of their porches the distinctive shade known as Haint Blue. Today, you’ll spot the color as building trim on small coastal cottages, and as the accent color on larger city dwellings along the Eastern Seaboard from the Carolinas to Florida as well. The blue that originally was derived from the Indigo plant has become an international favorite, and is a highly popular choice for home decor, particularly along the coast.

It’s a color that has also graced the porch ceilings of my homes — from Maine to Texas, and now in Arkansas — since I first learned about its history and its significance. It is said to ward off evil spirits. It is also believed to deter pests, particularly flies and mosquitoes. For those reasons alone, I would have chosen it, but the color is also calming and just unusual enough to appeal to me.

Besides that, it offers one more chance to tell a good story! I learned more about Haint Blue and its American roots during a trip last fall to Savannah and Tybee Island, Georgia.

The History of Haint Blue

In the early days of the American Colonies, the enslaved peoples from western Africa also brought with them the indigo seeds that thrived in their home countries. They grew well in the marshy sea islands along the Atlantic coast and the blue dye derived from the indigo plant became a cash crop for plantation owners, prized by the British in both the Old and New Worlds.

That distinctive blue retains its significance, although it appears today in a multitude of shades, from deep cobalt to a pale robin’s egg tint, from vibrant turquoise to a milky mixture of sky and sea with hints of grey or green. This historical affinity for blue is evident throughout the Low Country.

The African slaves toiled over indigo, along with cotton, rice and, later, tobacco. Following the Civil War, Gullah populations settled in communities along the coast, subsequently beginning the tedious job of “farming” the marshes for shrimp, oysters and crab. They also planted fruit trees and small vegetable gardens. Interestingly, it is the Gullah culture that can be credited for some of the more popular “Southern food” that we enjoy today.

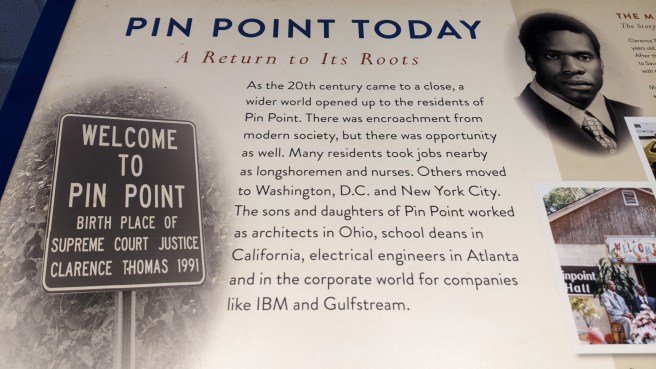

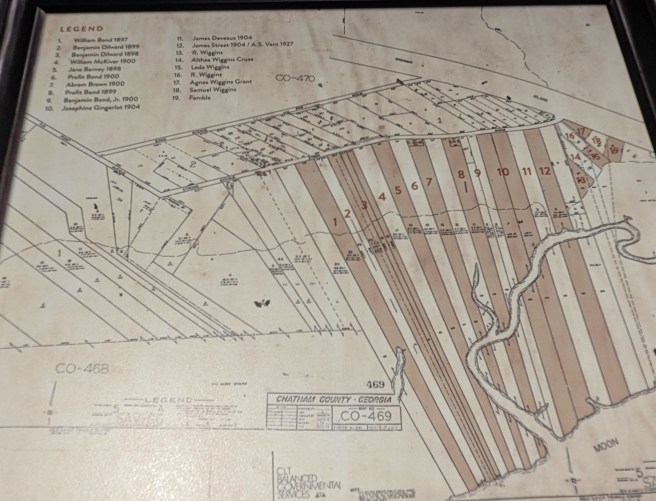

Waterfront property not far from Savannah that had been owned by Judge McAlpin as part of the Beaulieu Plantation was subdivided and sold to wealthy Savannah residents. Less-desirable marshy lots were made available to freed slaves who pooled their money to acquire long, narrow plots with limited access other than by boat through the marshes. The community of Pin Point was founded in 1896, and today it survives as the only Gullah Geechee community along the Atlantic coast that is untouched by commercialization.

Many of the newly-freed slaves remained on Skidaway, Ossabaw, and Green Islands as tenant farmers, crabbers and fishermen. However, a series of hurricanes swept through the barrier islands in the 1890s, killing many hundreds, if not thousands, of the inhabitants.

Pin Point is included in the swath of land from the Carolinas to northern Florida designated by the U.S. Congress in 2006 as the Gullah Geechee Heritage Corridor. Late last October, during the time of my visit to the area, a bridge to one of the coastal islands a bit further north collapsed during a Gullah Geechee celebration, killing seven people and injuring many more.

Against the Odds

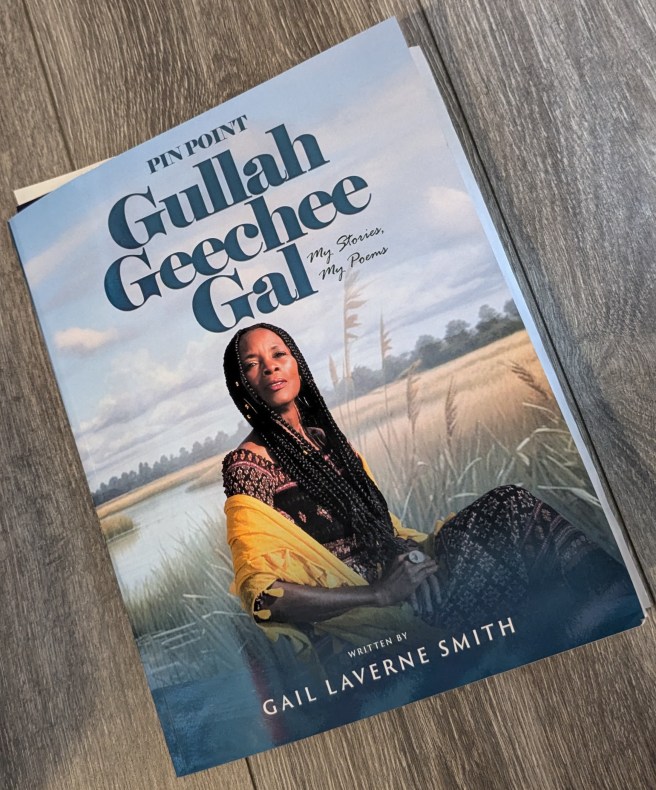

From the beginning, the story of Gullah Geechee communities has been one of survival against the odds. It was a hard life, but the newly freed families “made do,” according to Gail Laverne Smith, who was born in Pin Point, Georgia.

Smith’s recently published book, “Gullah Geechee Gal,” is a collection of stories and poems that speak of her life in the community.

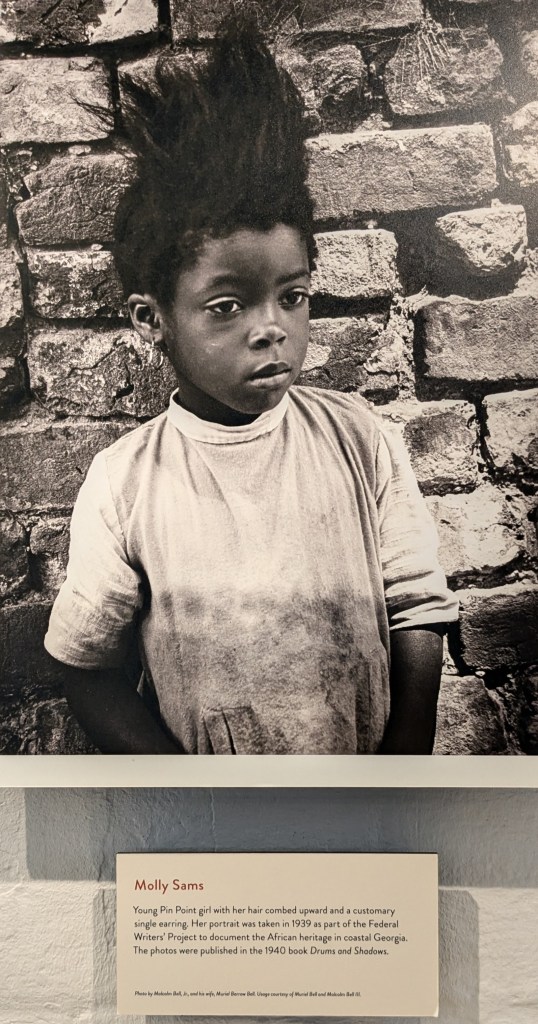

I met her at the Pin Point Heritage Museum, where she served as the Historic Interpreter. She spoke freely about her younger years as one of five children growing up in a community of fishermen, noting that they were “also skilled laborers who gathered to build homes, many of which were elevated on stilts to survive the heavy rains.” Known as shotgun houses, she explained that “when the front door opened, one could see clear through to the back of the house.” Other dwellings, including some of the first cabins in the community, were constructd of Tabby, a mixture of burned oyster shells, sand, water, and lime. A few still exist.

Today, about 100 residents still live in Pin Point, and the historic church and cemetery still serves local families. When the community was established, the first settlers built Sweetfield of Eden Church, an “offspring” of Hinder Me Not on Ossabaw Island.

In the 1960s, according to Smith, about 400 families lived in Pin Point. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas was born in 1948 to a Pin Point family. He was not only instrumental in the establishment of the cultural center, but is one of the featured former residents in the informative film shown to Pin Point visitors.

The Pin Point Heritage Museum

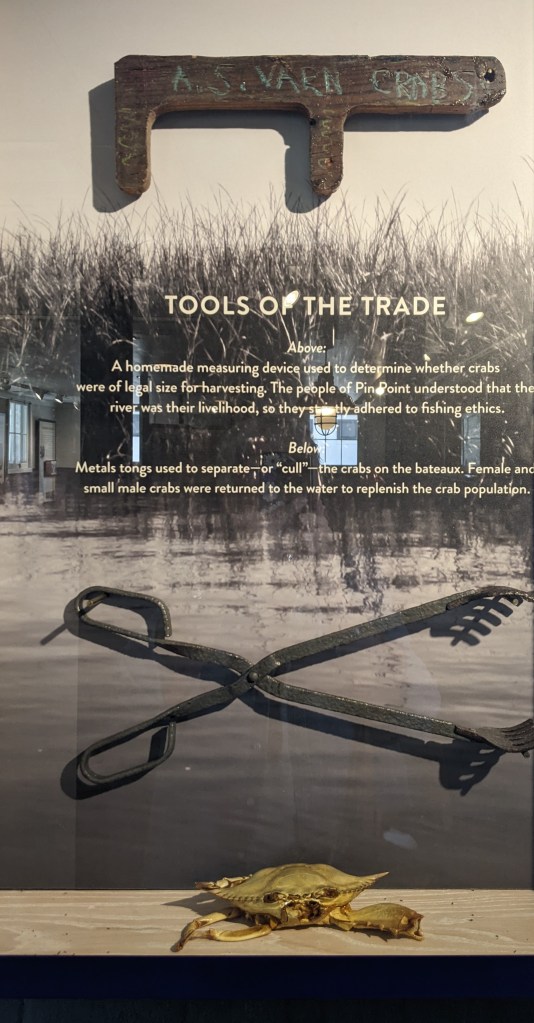

The educational center at Pin Point Heritage Museum is located in the former A.S. Varn and son Oyster and Crab Factory. Visitors are first treated to an introductory film, and then are free to explore the grounds at their own pace, learning about the factory’s operation during the years from its founding as a processing plant in 1926 until it ceased operation in 1985.

It was a strikingly sophisticated operation in its early years, with division of labor between men and women who performed the grueling work by hand. During the 1960’s, A.S. Varn was a major supplier of seafood along the Atlantic Coast. In the 70’s, however, a declining harvest and the rise of commercial fleets and factories contributed to its demise.

To learn more about Gullah Geechee communities and culture, visit http://visitgullahgeechee.com/about/.

Pin Point offers a fascinating glimpse of those former times, as well as insight into the Gullah Geechee community that existed there. Just up the road from the marsh, the still-existing community stretches to the site of the church and its nearly-century-old cemetery, offering insight into the past of this former freedman’s community and to the growth and development of coastal Georgia. Traveling on that isolated roadway was akin to taking a step into the past.

The newly-freed people who founded Pin Point were determined to preserve their heritage and maintain their cultural heritage and traditions. As Gail Smith explains, they have done just that. Religion and spirituality played a pivotal role in Gullah family and community life. Enslaved Africans were exposed to Christian religious practices, and they incorporated them into the traditional system of African beliefs. One of the prime values was that of community, according to Gail Smith.

She noted that, while growing up in Pin Point, children did not talk back to their parents —obedience and respect for their elders were primary requirements, as well as a belief that the needs of the community trumped individual goals and desires. She noted that the center of daily life and activity was the family, and that religious beliefs, hard work, and respect for nature held the community together.

In her book, Smith notes: “Growing up as a little girl in Pin Point, I always felt like even though we didn’t have a lot, we always had just enough.”

She continues to chronicle the cultural history and traditional lore of her community through her stories and poems. Her willingness to share her memories with visitors to Pin Point ensures that the voices of her ancestors continue to be heard and celebrated. The time I spent with her was evocative of a lifestyle and time I previously knew little about and I am grateful that I had the opportunity to learn about the Gullah Geechee heritage.

Celebrating Cultural Heritage

Geechee communities developed, over time, a distinctive dialect to maintain their individuality and partially confound the slave owners. A mixture of English, Creole French and some African words and expressions, the language is still spoken today by some of the Low Country families, and it partially defines the culture, in a similar manner as Haint Blue.

Pin Point is located just 11 miles from Savannah, situated adjacent to the marsh that separates it from Moon River. It is the last surviving black-owned waterfront community in coastal Georgia, one of the distinct communities that constitutes the Gullah Geechee National Heritage Corridor, the historic swath of territory established by an act of Congress in 2006.

That corridor is designated to ”help preserve and interpret the traditional cultural practices, sites, and resources associated with Gullah-Geechee people. It extends along the eastern U.S. coast through North and South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, culminating at the site of Fort Mose in St. Augustine, FL, which in 1738 was the first legally-sanctioned free black community in what would become the United States.

Today, the Gullah Geechee Corridor focuses on 79 Atlantic barrier islands in the designated area and certain adjoining areas within 30 miles of the coast. Traditional Gullah baskets woven from native sea grass are popular items at the Charleston market. Also, it is interesting to note that some of the typically “Southern dishes” that we enjoy today can be traced to the foods grown and consumed by the early Gullah inhabitants who not only caught fish, shrimp, crab and oysters from the sea, but also planted beans, rice and vegetables on their small plots of land.

The Gullah Geechee Corridor is administered through a partnership between the National Park Service, local governments, and cultural and tourishm authorities from the Charles Pinckney National Historic Site in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, just northeast of Charleston. If you’re interested in the area’s history, that site is also well worth a visit.