On April 12, 1961, Soviet Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to fly in space. The event not only made world news, but it reinforced American fears about being left behind in the technological competition with the Soviet Union.

Two and a half years earlier, the Soviet satellite Sputnik 1 had circled the planet for approximately three months before burning up as it re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. That was followed by dogs in space, a fly-by of the moon, a crash of the Soviet Luna 2 probe onto the surface of the moon, and the first photos of the dark side of the moon. All were Soviet accomplishments.

John F. Kennedy was elected President in November 1960. At the time, it seemed as if the Soviet Union had beat the U.S. into space before the term “space race” had even been voiced.

Then, in an address to Congress and the Nation on May 25, 1961, President Kennedy proclaimed: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.”

At the time, it seemed an audacious, if not impossible, dream. But the mood of the nation was energized and hopeful.

Plans were made for two new rocket launch complexes north of Cape Canaveral in Florida, although construction of the enlarged Launch Operations Center wouldn’t begin until November 1962. Land was set aside near Houston for what was to become NASA’s Mission Control Center. The new president wasn’t about to let the other side gain further advantage. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration had already established the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama.

The Race to Space Had Begun

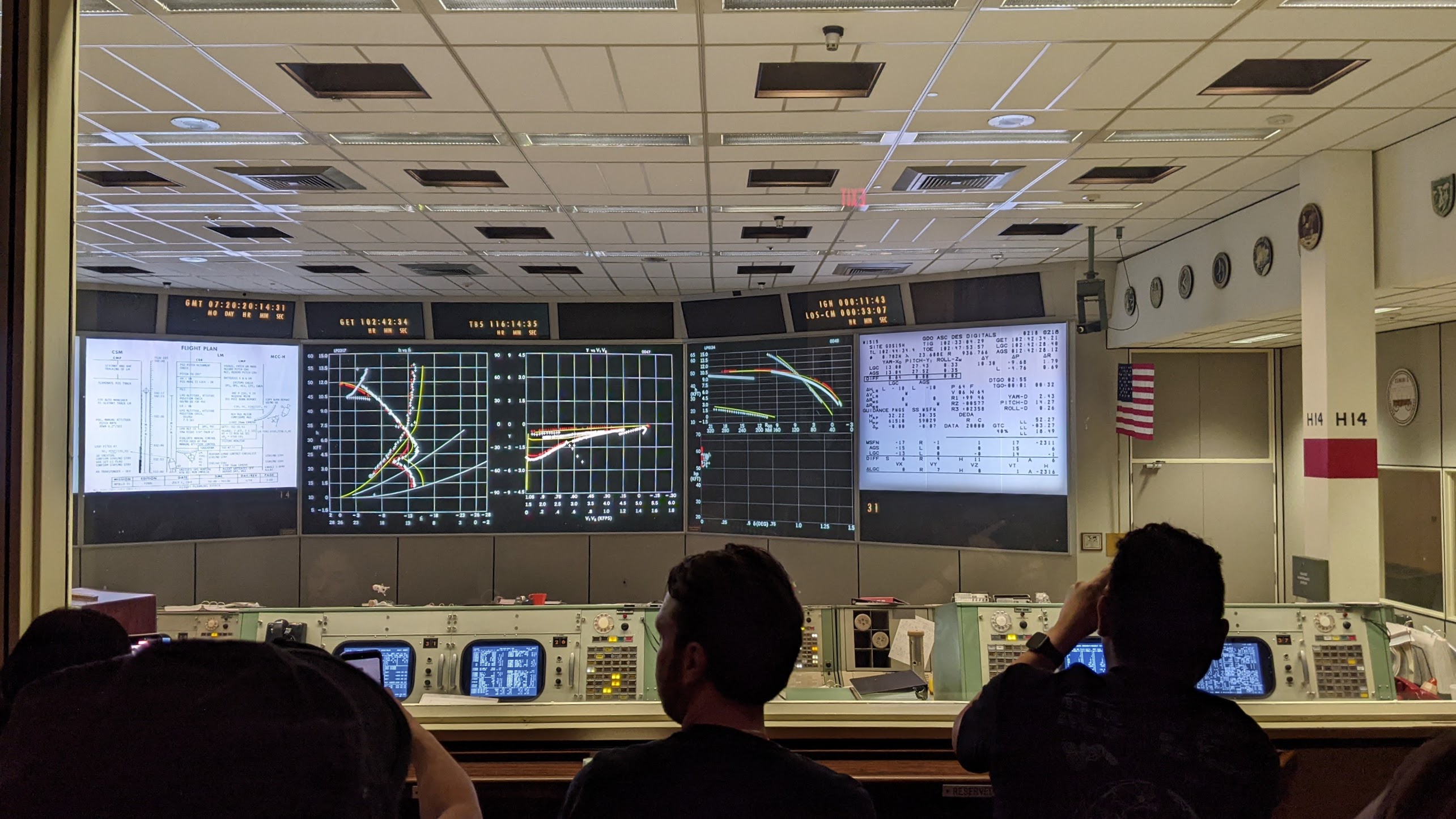

My visit to Space Center Houston included a tour of the Mission Control Center in use for most of the country’s early space flights, including the first moon landing in 1969. It has been preserved as it was then — down to cigarette butts in ashtrays, Styrofoam coffee cups amidst the banks of monitors and scattered about on the floor, a few black desktop telephones with curly cords, and bulky vintage computers.

Today, the room looks somewhat like a movie set. Stadium seating behind a wall of glass allows visitors to see the array of desktops and equipment. For those of us who watched that first landing in real time, it was eerily familiar.

Visitors watch the broadcast tape from July 20-21, 1969, replayed on a wall-mounted TV screen. Listening to the raspy voices of mission control directors and news reporters, I was transported back to that time. I nearly teared up once more as veteran television commentator Walter Cronkite appeared overcome with emotion. I couldn’t resist mouthing the words: “The Eagle has landed.”

First Men on the Moon

In quick sequence, I relived the disbelief, the awe, and then the jubilation of that July day. I almost forgot that it had happened 55 years ago.

The first words spoken by Neil Armstrong were unclear: “One small step for . . .” Did he say man or a man? And then, “One giant leap for mankind.”

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin followed Armstrong, stepping out of the lunar lander onto the moon’s surface approximately 20 minutes later. The lander itself was an odd sort of taxi from the orbiting Apollo spacecraft to the moon’s surface. With spindly “toothpick” legs, it seemed held together by aluminum foil and chewing gum. Pilot Michael Collins remained aboard the Apollo command module Columbia in orbit around the moon.

The lunar lander was on the surface of the moon for about 21 hours, and the two astronauts didn’t venture far from the landing site, dubbed “Tranquility Base” by Armstrong. They did, however, plant the first American flag on the surface and they collected more than 45 pounds of moon rocks before reboarding Eagle. When they returned to Columbia with their payload, the lander was jettisoned to fall back onto the surface of the moon.

The Apollo 11 mission that brought these first humans to the moon was just the fifth crewed mission of the Apollo program. Six Apollo missions actually included moon landings, and Armstrong and Aldrin were the first of only 12 men to step onto the moon’s surface.

Ever!

The final moon landing was a 12-day Apollo 17 mission in December 1972, just a little over three years after Apollo 11.

NASA Today

The current mission control center is still located in the same building at Johnson Space Center, just a floor or two below the original. Our group did not visit, but I expect it is sleekly outfitted with an updated array of wireless communication technology necessary to monitor today’s space launches and landings.

The grounds of Johnson Space Center, however, are “littered” with reminders of early American space exploration.

Marvel at the immense Saturn rocket that carried Apollo astronauts into space. The 30-story tall rocket was displayed outside and upright for two decades, but it suffered “weather abuse,” so it has been restored and is now displayed horizontally in a specially constructed building.

I gasped at the size of the five immense thrusters on the Saturn V. It is one of three intact Saturn V rockets that still exist, and it stretches for what seems like blocks, while flags and story boards chronicle NASA’s 17 Apollo missions, both the successes and the tragic failures. It’s a sobering experience.

Learn the history, from initial pre-orbital flights through later missions used to transport men and supplies to the orbiting Skylab, launched into orbit in 1973.

Then, move on to the space shuttle era.

Between 1981 and 2011, American shuttles successfully completed 135 missions and carried 355 astronauts from 16 countries. My husband and I were observers twice for shuttle launches, including the last flight of Space Shuttle Discovery in February 2011. Discovery was the third of five shuttles built, and the first to be retired. The U.S. shuttle program was discontinued later in 2011, with the final flight of Shuttle Atlantis.

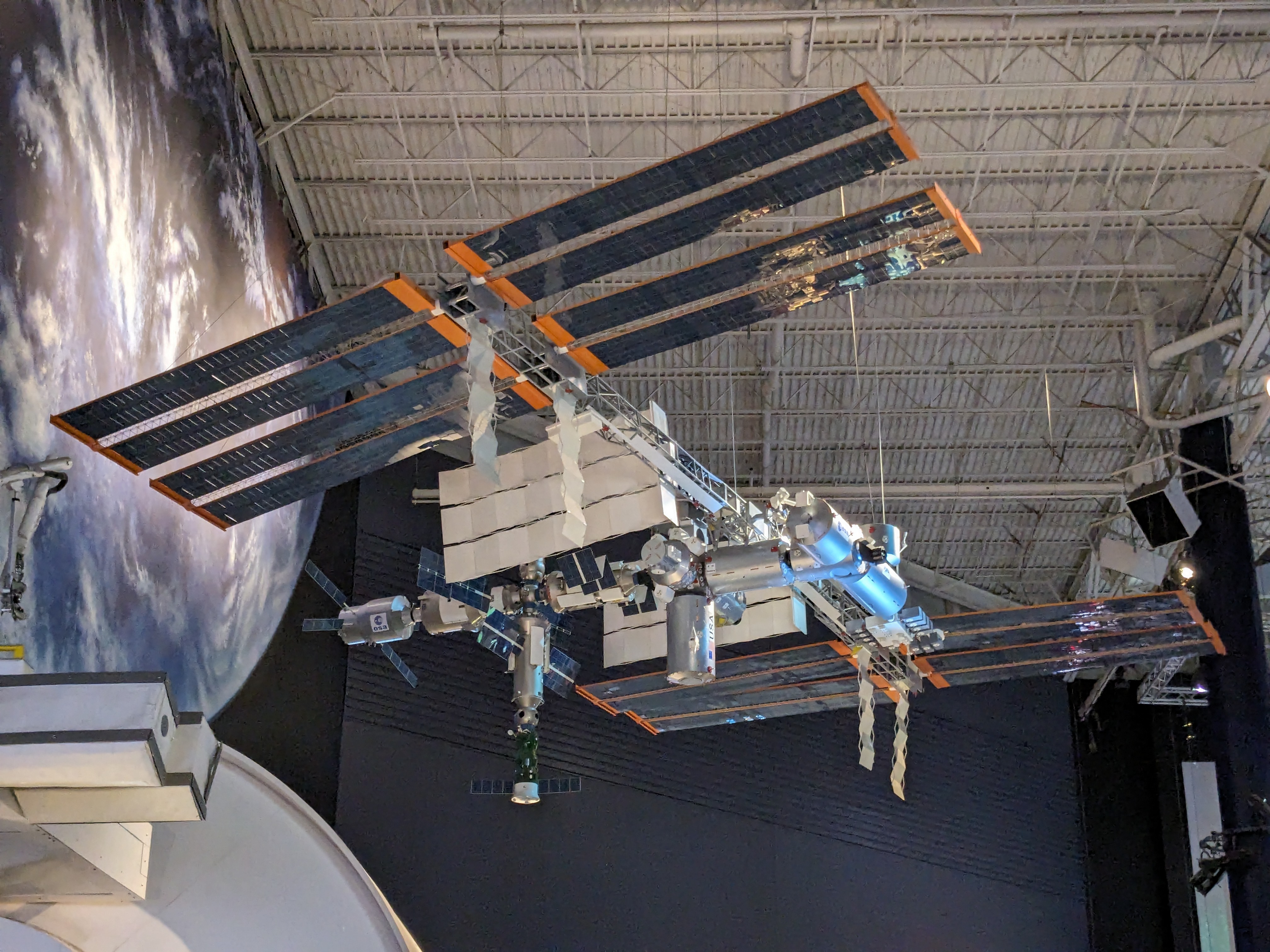

Get close to a full-size Boeing 747 aircraft with a sleek white space shuttle on its back. It rests in a peaceful field, adjacent to a herd of grazing Longhorn cattle. The reusable, winged spacecraft was designed to carry large payloads and crew into orbit. It was instrumental in the development, initial outfitting, and staffing of the International Space Station (ISS). Crews have lived and worked aboard the ISS continuously since the year 2000. Today, however, NASA cooperates with other nations and private companies to transport crews and supplies to the space station.

Walk through the outdoor “rocket garden,” then spend as much time as you wish in the Space Center Museum to learn about NASA’s past and future missions. Make time to visit interactive exhibits or to attend a lecture. I found it interesting to learn about meal preparation in space.

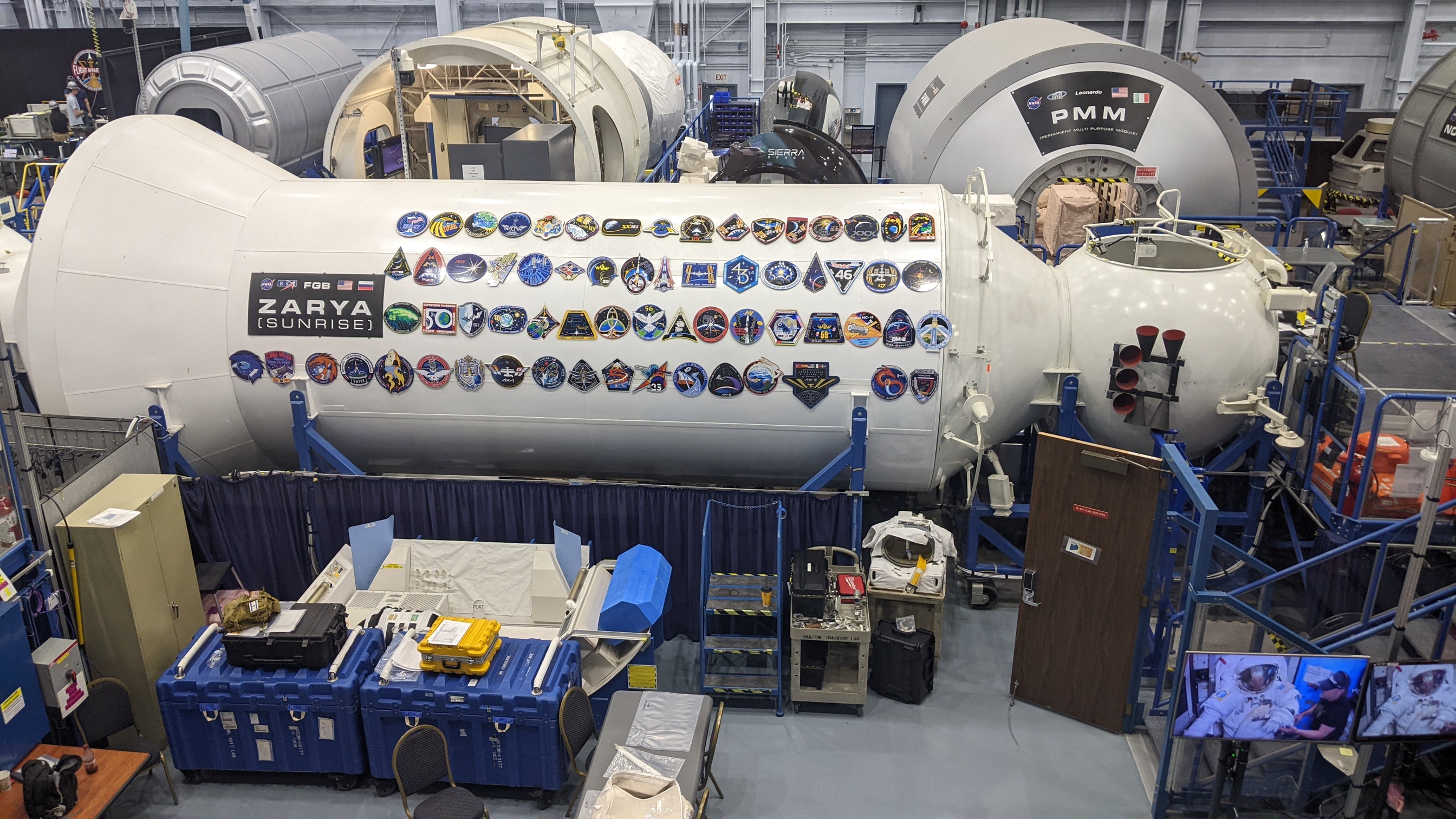

My tour also included a walk along a raised catwalk to peer down at the floor of a huge astronaut training center with full-size replicas of space station modules and transport capsules that journey to and from the space station. Although I am certain it can become a hub of activity at time, it appeared quiet and relaxed the day we visited.

Anticipate Future Exploration

Many more space missions are planned, but they will be very different.

First, according to NASA, the United States will return to the moon, perhaps as early as 2026. The ISS is set to be “retired” and dismantled by 2030, replaced by two or more international orbiting space stations, likely to be commercial or privately financed ventures. Then, American astronauts and the international community will turn their sights towards Mars and beyond.

The Artemis Accords, a set of principles designed to foster international partnerships for space exploration, were conceived and signed by representatives of eight nations, led by the United States, in 2020. To date, 42 countries have signed the voluntary agreements.

At Home on the Prairie

The NASA site is well-integrated with its Texas prairie roots. The agency has been working on sustainability projects in one form or another for more than 20 years. In addition to the Longhorns that share the 1,600-acre campus, the Johnson Space Center hosts a Houston Zoo program dedicated to increasing the population of endangered Attawater Prairie Chickens. The birds are bred in onsite field pens in an area that resembles their native habitat.

Another unique feature offers employees free access to more than 300 bicycles while on site to provide emission-free alternatives to driving while on the campus that’s adjacent to Clear Lake, which flows into Galveston Bay. During heavy rain, flooding and associated pollution can occur, so the space center has installed mitigation measures to alleviate potential problems and avoid disruption of operations. While NASA continues to have its sights set on space missions, it is also serious about protecting the home planet.

Visiting the Space Center

Space Center Houston is said to be the Number 1 attraction for foreign visitors to the Houston area. Leave plenty of time for your visit. There is much to see. One could easily spend an entire day in the exhibit hall, and tram tours of the 1,600-acre campus are offered.

The center brings alive the history of American space efforts, from the first sub-orbital flight of Alan Shepard in 1961 and John Glenn’s three orbits around the Earth in 1962, to future planned Mars missions.

It is affiliated with the nation’s Smithsonian Institution and is one of several locations where visitors can learn about the U.S. space program. Visitor centers are located throughout the country, including Kennedy Space Center in Florida and the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. A Space Camp is also held at Marshall.

If you’re interested in the full story of flight, the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C, should be on your list. And, if you’re visiting the Midwest, a side trip to the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas, is well worth a visit. There, you can see a full-size Blackbird spy plane and “Liberty Bell 7,” the Mercury capsule that sank in the Atlantic upon splashdown after a successful 15-minute sub-orbital flight in 1961. The accident almost killed Astronaut Gus Grissom, the second man in space. The account of its retrieval and restoration is legendary.